Letter to Governor Gavin Newsom | Housing Crisis | California Housing Crisis | Fix Housing Crisis | Housing Crisis USA

Letter to Governor Gavin Newsom | Housing Crisis | California Housing Crisis | Fix Housing Crisis | Housing Crisis USA

Letter to Governor Gavin Newsom | Housing Crisis | California Housing Crisis | Fix Housing Crisis | Housing Crisis USA

Letter to Governor Gavin Newsom | Housing Crisis | California Housing Crisis | Fix Housing Crisis | Housing Crisis USA

Letter to Governor Gavin Newsom | Housing Crisis | California Housing Crisis | Fix Housing Crisis | Housing Crisis USA

Governor Gavin Newsom

Office of the Governor

1021 O Street, Suite 9000

Sacramento, CA 95814

Cc: Rob Bonta, Scott Weiner

Dear Mr. Newsom,

By way of introduction, I have been a California native and resident of the Bay Area since 1999, first in San Francisco and most recently in Sausalito, where I live with my wife and two young boys. In 2015, we bought a house with significant deferred maintenance issues, and after spending seven years renovating it for our family, finally moved into the finished home in December 2021.

My wife and I have experienced firsthand how difficult and restrictive it can be to build or remodel anything here in Southern Marin. Our original renovation plans were for a single-family home, which we modified to include an accessory dwelling unit. We are not developers of market-rate or affordable housing, but we’ve realized that many of the tactics that the “stewards of existing conditions” put forth in objection to new housing can afflict any type of developer in this state. And I see that this municipal-level, local resistance is leading to palpable changes in local demographics, reducing our ability to fight air pollution and increasing race-based exclusion from certain communities. Personally, I have friends who have left California for other states because of the high housing costs here.

Remodeling single-family home

A quote you provided to Ezra Klein in late 2021 stands out to me:

The reason we began suing cities was to provide air cover. I can’t tell you how many mayors privately thanked me even as they publicly criticized me for those lawsuits. We’re trying to drive a different expectation: We will cover you. You want to scapegoat someone, scapegoat the state. We haven’t had that policy in the past. Localism has been determinative. And that’s part of what’s changing.

Localism is an apt phrase for what my wife and I have encountered. And for the last seven years, I have wondered — how is this happening? How are small groups of “Neighborhood Defenders” able to bully, trick, or cajole elected and appointed city officials into thinking that their voices of objection are representative of the community at large? And delay, delay, delay projects until the “sponsors of proposed conditions” give up and go bankrupt?

I’ve tried to learn from our experience and develop pragmatic plans of action that might be of use to you and your team to tackle this dynamic — specifically in the more white, affluent, exclusive communities that are most responsible for choking new housing development in this state.

Here are the initiatives I’ve identified, for which I’ve provided more detail below:

- Require municipalities to send all design/discretionary review data related to proposed projects and their evaluations to a centralized (state-run) public repository

- Repeal the Brown Act and start over with something better

- Eliminate municipalities’ ability to indemnify themselves as a condition of approval

Require Planning Commissions to send all data related to proposed projects and their evaluations to a centralized (state-run) repository

The NRA’s PAC group has a well-known report card rating politicians’ stances and voting records on gun rights, which gets rolled out every election cycle. They use a quantitative methodology that incorporates how a given politician voted, not just what they said.

What if we could do the same for a politician’s stance on new housing — market rate, or affordable, or both — based on their voting record for their precinct? For example, we could use an analysis similar to what UC Berkeley David Brockman, along with Vitor Bacetti and Alex Taylor, created for San Francisco District 5 supervisor Dean Preston’s voting record on new housing projects (“Dean Preston’s Housing Graveyard,” https://nimby.report/preston).

Here is Dean Preston’s actual voting record from Q4 2019 to Q4 2021:

|

Total Homes (including market-rate) |

Affordable homes | |

|---|---|---|

| Homes Approved | 602 | 109 |

| Homes Opposed | 30,051 | 8,561 |

Of course, what Dean Preston says about housing, and affordable housing in particular, bears no resemblance to his record. This looks like an “F” to me.

I tried to do something similar with the Sausalito Planning Commissioners and City Council members (when they were required to vote on design review appeals).

What I found was an extremely variable set of voting records.

Table 1: Voting record over the active years of each Planning Committee member from 2013-2020

| Planning Committee Member | Approval Percentage | Denial Percentage | Continued Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| PC1 | 75.0 | 0.0 | 25.0 |

| PC2 | 52.0 | 10.0 | 36.0 |

| PC3 | 55.0 | 2.5 | 40.0 |

| PC4 | 52.1 | 6.6 | 40.5 |

| PC5 | 53.1 | 6.3 | 37.5 |

| PC6 | 48.4 | 3.8 | 43.2 |

| PC7 | 46.2 | 6.3 | 42.7 |

| PC8 | 46.7 | 5.9 | 46.1 |

| PC9 | 46.1 | 5.3 | 42.1 |

| PC10 | 42.7 | 6.5 | 44.4 |

I also looked at the voting records of the City Council members pertaining to design review appeals, which again showed a high level of variability.

Table 2: Activities of City Council members (Approved a Planning Commission denial / Denied a Planning Commission approval)

| City Countil Members | Approved a Planning Commission Denial | Denied a Planning Commission Approval | p-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | TOTAL | Yes | No | TOTAL | ||

| CC1 | 4(30.8) | 9(69.2) | 13 | 10(58.8) | 17 (41.2) | 17 | .127 |

| CC2 | 13(100) | 0(0.0) | 13 | 17(100) | 0(0.0) | 17 | - |

| CC3 | 5(38.5) | 8(61.5) | 13 | 6(35.3) | 11(64.7) | 17 | .858 |

| CC4 | 2(16.7) | 10(83.3) | 12 | 10(58.8) | 7(41.4) | 17 | .023 |

| CC5 | 1(7.7) | 12(92.3) | 13 | 1(5.9) | 16(94.1) | 17 | .844 |

| CC6 | 8(61.5) | 5(38.5) | 13 | 5(29.4) | 12(70.6) | 17 | .078 |

| CC7 | 11(84.6) | 2(15.4) | 13 | 11(64.7) | 6(35.3) | 17 | .222 |

| CC8 | 6(46.2) | 7(53.8) | 13 | 7(41.2) | 10(58.8) | 17 | .222 |

| CC9 | 1(7.7) | 12(92.3) | 13 | 6(35.3) | 11(64.7) | 17 | .077 |

I then tried to analyze their voting records specific to the findings that could not be met for continued and denied projects, and the data was all over the place. No consistency, nor any clear objective rationale, was evident.

A commonly voiced sentiment was, “We do want more affordable housing available here in Sausalito, but just not this particular project.” Eerily similar to the language we’ve seen used across the Bay in San Francisco.

But I had to do all of this analysis by hand. Meeting minutes, videos. The way the data is structured and organized on a city’s website might be useful for meeting the requirements of the Brown Act, but it is abominable for anyone trying to derive any meaning from it in aggregate.

My takeaway is that the way Sausalito documents its design review data is actively helping the City obfuscate its haphazard and subjective decision-making for those who wish to understand it.

If I, as a voter, knew the voting record on new housing projects for each City Council and Planning Commission member (the Planning Commission being a common entry point to the City Council), it would be enormously helpful in picking a pro-growth candidate based on objective, quantifiable data. I could make a housing report card for each candidate. But as it is, all we have is what the candidate says about their thoughts on new development, which is squishy.

Good data is dangerous because in the hands of someone who knows how to ask the right questions, true insights can be derived from it. And with insights can come recommendations for action — data-driven recommendations. Municipalities know this and will likely fight, drag their feet, or otherwise make their data indecipherable because they know you might very well find something of use in that data. Put an uncomfortable spotlight on certain appointed and elected officials that repeatedly shut down new proposed development.

There are challenges. An entity that is forced to reveal information (and doesn’t want to) can make its numbers unanalyzable by using confusing and inconsistent data formats, classifying things in different ways, or providing partial data sets.

Here’s an example.

The Hospital Price Transparency Act was designed to “help Americans know the cost of a hospital item or service before receiving it” (source: CMS). This was noble in its aim but terrible in its execution. The reason? There’s no way a hospital is going to want to let the public know their charge-to-price ratios, what their profit margins look like, or how good (or bad) their contracts with insurance companies are. As a result, you have both non-compliance with the law and bad data. The lesson here is that you need to define and enforce a consistent set and frequency of data transfers to the state’s repository. Set up a reliable, validated electronic data interchange and enforce its use.

So what sorts of things are we looking for, and why?

What if your Housing Strike Force could see and track the progress of proposed projects in real time? And get ahead of potentially disastrous outcomes rather than intervening after the fact? For example, your Department of Housing and Community Development investigation into the 469 Stevenson Street debacle (where the San Francisco Board of Supervisors rejected a proposal to turn a downtown parking lot into 500 housing units) was initiated over one month after the final vote on the appeal. What if each board member was publicly required to record and publish which findings could not be “met,” alongside their vote of continued or denied? You’d be able to discern much more quickly, right after the first hearing, whether the Supervisors were heading in a direction inconsistent with the Housing Accountability Act. Your Housing Strike Force could mobilize — let the Commissioners know that they’re breaking the law, and arm the sponsor with legal and other support.

In addition, if it was possible to scrape the noticing agenda and associated documents from these municipal websites in real time, high-risk, larger-scale projects could be identified before the first hearing ever occurred. Representatives could then attend those meetings — I have seen examples where the mere presence of a CaRLA (California Renters Legal Advocacy and Education Fund) attorney so terrified the City that they ruled in favor of the proposed project in order to avoid the possibility of a writ.

Repeal the Brown Act and start over with something better

The Brown Act is a law that aims to do good, but in reality, I am convinced that it is hindering housing growth in California.

In September 2021, a local City Council member stepped down from her elected role as a Novato City Council member. She explains her rationale:

As a medical professional, I have seen firsthand the short- and long-term effects of stress and I am unwilling to subject myself to it any longer. … When I began my term, I looked forward to working collaboratively with my colleagues on the City Council. However, due to a combination of severe restrictions imposed upon us by the Brown Act and the shutdown precipitated by the COVID epidemic, this has hardly been the case.

Instead, I have found that we work as government by silo. We have only had three in-person meetings in my almost two-year tenure and we are not allowed to meet with more than one council member at a time to discuss matters outside of those meetings. It seems like we have been addressing one five-alarm fire after another without a workable path to resolving so many of the issues that have been raised.

I have a joke for you, Mr. Governor. It goes like this:

A City Council member, a concerned citizen, and the Brown Act walk into a bar. The City Council member walks to the bar, takes a seat. She’s followed by the Brown Act, who takes a seat to her right. Last is the concerned citizen, who sits next to the Brown Act.

Awkward silence. And then you finally give in.

“OK, what’s the punchline? What happens?”

“Absolutely. Nothing.”

The Brown Act makes it near-impossible for a local government to function effectively and especially to develop longer-term strategies. And what it also does, in its operational reality, is make open communication between the Planning Commission or City Council and a project sponsor, applicant, or citizen next to impossible.

During so many Planning Commission meetings, I wished fervently that the Commissioners could just tell us what was OK to build, not was not OK to build. Continuances are extremely expensive, and I believe the Brown Act is directly responsible for costing developers hundreds of millions of dollars in this state.

Since the Brown Act was signed into law 70 years ago, it has proven to have disastrous unintended consequences. It is a failed experiment, and it needs to be repealed.

Eliminate municipalities’ ability to indemnify themselves as a condition of approval

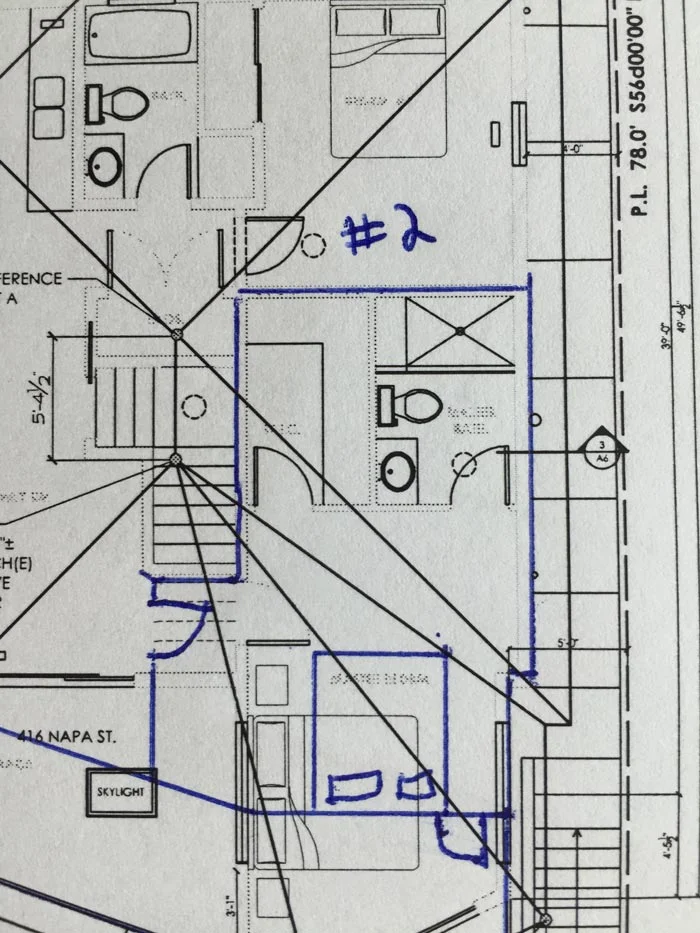

One legal liability I was surprised we had been encumbered with was an indemnification clause, number ten on our conditions of approval:

Applicant shall defend, indemnify (including reimbursement of all fees and costs reasonably incurred by separate counsel retained by the City) and hold harmless its elected and appointed officials, officers, agents, and employees, from and against any and all liability, loss, damage, or expense … arising from the City’s approval of the project.

I called up the City Attorney and asked politely whether I could please strike out this indemnification clause from the document as I did not agree to this term as part of our application. I was told via email that “it is a standard condition of approval that the City has been applying consistently for years. We also discussed the fact that numerous other jurisdictions including other Marin County jurisdictions apply similar conditions. … It is important to note that there is other support for the City’s position that the condition is enforceable.”

The City Attorney answered my question of “How is it legal that you are able to do this to proposed projects?” by basically saying, “This is how we’ve always done it, it’s how others do it, and you better believe we can enforce it.” Also, that we had implicitly agreed to this condition when we applied for our design review.

This is a very real risk for developers, who, within 35 days, can be exposed to a CEQA action or a writ that is filed within 90 days of the official project approval. The idea that a sponsor should have to shoulder the risk and expense of defending a city’s decision is absurd.

So, to meet the objective of de-risking proposed projects for developers to make them more financially viable, state-level legal action should be taken to eliminate the legal ability of a municipality to indemnify itself from a lawsuit arising from one or more of its own Land Use Entitlement Design Review decisions. These indemnification clauses are cowardly vehicles because if a municipality grants its elected and appointed officials the power to make decisions that affect people’s lives, it should itself take legal responsibility for the decisions and actions of its elected and appointed officials.

If litigation is brought against an approved project, it should not be the developer who has to fund and litigate on behalf of the City to protect what the City approved. The officials themselves can be indemnified — otherwise, nobody would want to hold public office — but the City cannot be. This can be the “With Great Power Comes Great Responsibility” act.

In Closing

I’ve tried to locate any state committees, task forces, or other commissions that, as part of their remit, would investigate and potentially pilot some of the ideas presented above, and have been unsuccessful. It appears they do not exist.

Therefore, my recommendation would be to create a new agency in the California Department of Housing and Community Development that might investigate some of these alternative approaches. Create a Housing Innovation Squad to work closely alongside Attorney General Rob Bonta’s Housing Strike Force and other internal teams. Define the Squad’s charter, develop a budget, and develop clear, time-bound key performance indicators that, if not met by the pre-specified time, mean the dissolution of the Squad.

What do you have to lose?

You might find that, outside of the censorious ears and vitriolic voices of the local electorate, there are yet more mayors and City Council members who will thank you in private for your efforts to address this housing crisis.

Respectfully yours,

Matt H. Smith