If you’re looking for extreme (versus moderate) sentiment, the comments section beneath a news article or posting is where you’ll find it. And invariably, when an article is posted on a proposed new pro-housing law or proposed development, you’ll get comments like the one below:

“These people are threatening our way of life. I grew up lower middle class, worked my way through school, and worked hard to buy a home in Marin thirty years ago. I have no tolerance for people that want to cram more people in our beautiful city with these ugly, monstrous apartment complexes that will destroy the neighborhood character and destroy my property value.”

“Ugly.” “Monstrous.”

There’s a lot to unpack with this prevalent set of perspectives, but there’s one in particular that’s important to dwell on — that of design and good architecture. The fear that some unsightly forms will cover what was once familiar and beautiful. For some reason, it would appear that many NIMBYs are under the impression that any new multi-unit or affordable housing development will be unsightly. That anything other than a single-family home would be architecturally and culturally incompatible with the “neighborhood character.”

In the spring of 2021, my wife and I took a vacation to Seattle — we hadn’t traveled in a long time, and it seemed as fun a city as any to visit. And it was accessible from a tiny airport in Sonoma County that I loved flying out of.

One of the day-tripping activities we decided to do was take a ferry ride to nearby Bainbridge Island and explore the place a little, very much like how San Francisco tourists take a ferry ride to explore Sausalito.

We were dropped off in the downtown district, an amazing strip of cafés, bookstores, and little shops with beautiful parks dotted all through the area. There were incredible views of Mount Hood and Seattle in the distance of the Sound. But, after walking around the town a bit, I noticed something interesting about the buildings — there was an abundance of multi-unit housing interspersed among the single-family structures. It looked very well-designed, with well-designed landscaping. This mixed housing, what has been called “the missing middle,” had been designed to create — to me anyway — an idyllic scene.

How did Bainbridge pull this off? How had it crafted such a warm, beautiful, and inviting “neighborhood character” mixing historic and modern structures?

Back at home, I studied Bainbridge Island a little. I learned that as early as 1994, their general plan had a significant section devoted to building both market-rate and affordable housing.

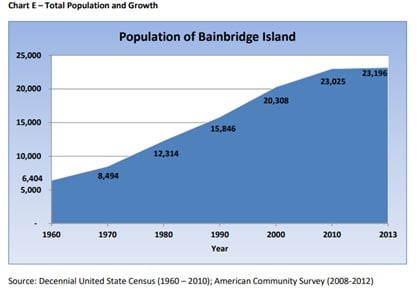

The town had been able to flex to meet the needs of an increased population, which had almost doubled between 1980 and 2013.

Where were these new people living? Had housing growth kept up with population growth? It would have to, right?

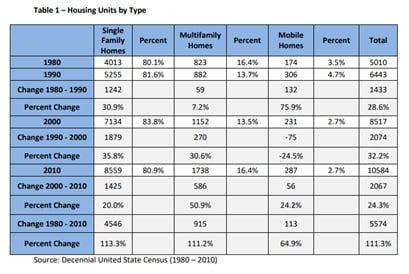

Bainbridge Island did, in fact, build to meet the housing needs of the new residents. Between 1980 and 2010, there was a total 113% growth in housing units. But what makes this growth especially remarkable is that the growth rate of multi-unit housing matched that of single-family housing.

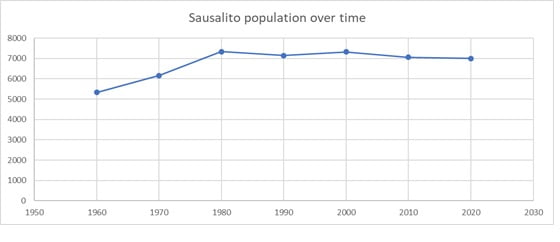

Now when we look at Sausalito during the same time frame, we see basically zero population growth between 1980 and 2020. Of course, if new housing and infrastructure isn’t built, new people can’t move there.

Much of Marin mirrors the population stagnation seen in Sausalito during this period. And with no new people coming in, what emerges is a mostly white, affluent, exclusive community.

When you restrict growth, you get Marin, one of the most racially segregated counties in the state.

But good architecture is expensive. If we want to build more affordable housing more cheaply, might there be ways we could make great design more financially accessible to the developer?

Going back to the angry Marin resident quote, speaking to “ugly, monstrous apartment complexes,” what if that wasn’t the case? What if an argument could be made for world-class multi-unit housing design that was affordable?

Nobody wants to see bad design, or design inconsistent with its surroundings. But good architects are expensive. How do you make excellent architecture available to a budget-minded developer?

———

In October of 2018, an artificial intelligence-created abstract portrait sold at Christie’s New York for $432,500. A machine created that portrait using a methodology pioneered by Ian Goodfellow, dubbed “Generative Adversarial Networks.”

Jason Brownlee of Machine Learning Mastery describes this approach:

Generative modeling is an unsupervised learning task in machine learning that involves automatically discovering and learning the regularities or patterns in input data in such a way that the model can be used to generate or output new examples that plausibly could have been drawn from the original dataset. GANs are a clever way of training a generative model by framing the problem as a supervised learning problem with two sub-models: the generator model that we train to generate new examples, and the discriminator model that tries to classify examples as either real (from the domain) or fake (generated). The two models are trained together in a zero-sum game, adversarial, until the discriminator model is fooled about half the time, meaning the generator model is generating plausible examples. [1]

What if there was a way to use this process in creating a design for a new housing development? How would you start?

There exists a rich trove of highly valuable data sitting in standardized and structured data formats that are freely accessible to anyone with an internet connection. Hundreds of world-class architectural and structural designs — tens of millions of dollars in the making — rendered in a beautifully consistent format that you only see with highly formalized documents. It is delicious and nutritious machine food, all available for download at Sausalito.gov.

Almost all of these designs are for single-family homes, but that’s no reason they can’t be used for multi-unit design.

The designs reflect the latest in engineering technologies and illustrate creative, world-class approaches to building structures in very challenging and hilly terrain, and moreover, are stored in a very accessible machine food format (pdf). All have been reviewed, vetted, and approved for adherence to federal, state, and county codes. Designs constituting hours of work from structural engineers, builders, architects, and others are freely available.

What makes these datasets so amenable to machine consumption? The data is highly structured. Unstructured data is one of the scourges of machine learning nutritionists, while structured data is exceptionally nourishing to a hungry and curious machine mind. Every page is strictly rendered along a clear and consistent scale, and the sequence of content is homogenous from one set of plans to the next. Symbols are consistently used, and all the design elements adhere to a common set of graphic standards and conventions. And it’s not just the exterior of the proposed project — you have interior elevations in there as well. This includes cabinetry, vertical dimensions, trims, and window casings, all self-referenced so the machine can reference these interior views in the context of the larger plan; hardware and door schedules, electrical, gas, and water designations; finish schedules; and applicable codes, standards, and guidelines. You could not ask for a more wholesome feast for your machine.

Your machines don’t necessarily need to know what the function of a door is, just understand that every room has at least one, that they have a certain size relative to certain design elements, and that they need to be designed to be closely concordant with the “real” plans. If you own a plot of land and want to build a new home on it, or have an existing house you’d like to improve, imagine being able to input a series of site conditions, neighboring structures, and other contextual data, and put your preferences into a system that could automatically create a plan set for you. Is your house on clay, sandy loam, other? What is the size and location of your lot? What does the site grading look like? The climate? Sun exposure? What sort of structures surround the property? Where are the windows and decks of neighbors, so you can design around privacy issues? And then the house preferences: colonial, modern, beach home, craftsman, other? Do you want a Jack-and-Jill bathroom setup for the kid’s bedrooms? Where do you want the focal point to be — a large and open kitchen, an expansive family room? Assuming you as the owner are content with having your home designed by the collective intelligence of world-class architects and other professionals, you could find yourself with an inexpensive, quickly rendered, code-compliant, beautiful set of plans to take to your builder. You could do all of this with the structured data in the plans.

A question then comes up — is it ethical or legal to derive plans based on the work of others? If I train a machine to create a landscape in the style of Matisse and sell it, do I then have to pay Matisse’s estate some sort of fee? Right now the legal answer is no. As of 2022, the Brown Act allows anyone to access a set of building plans because they are connected to a public meeting — the design review.[2]

We’re trying to find ways to lower costs, increase certainty, and decrease the time it takes to build. With this approach, what once took hundreds of thousands of dollars and six months to a year to create, could be done for 10% of the cost, and in 10% of the time. You’d still need a staff architect to supervise the machines, but I cannot see a future where this approach would not be employed.

There’s no reason to think that multi-unit housing will be as architecturally stunning as fancy single-family homes. This is an unfortunate stigma, and one that needs to be overcome. Fortunately, there might be some tricks using a “narrow AI” approach that can help get us there.

[1] https://machinelearningmastery.com/what-are-generative-adversarial-networks-gans.

[2] “CA. Gov. Code § 54957.5(a)”. California Legislative Information. State of California. Agendas of public meetings and any other writings, when distributed to all, or a majority of all, of the members of a legislative body of a local agency by any person in connection with a matter subject to discussion or consideration at an open meeting of the body, are disclosable public records under the California Public Records Act (Chapter 3.5, commencing with Section 6250 of Division 7 of Title 1), and shall be made available upon request without delay.

Neighborhood Character Neighborhood Character Neighborhood Character Neighborhood Character Neighborhood Character Neighborhood Character Neighborhood Character Neighborhood Character Neighborhood Character Neighborhood Character Neighborhood Character Neighborhood Character Neighborhood Character Neighborhood Character