Letter to Sausalito Housing Element Update Committee | Housing Crisis Marin County | Housing Crisis California | Housing Renovation Sausalito | Housing Renovation Crisis Sausalito | House Design Review Sausalito.

Comments On The August 5th Sausalito Housing Element Update Meeting where we take a deeper look into what . . . Sausalito Housing Element Update Meeting | Sausalito Housing Element Update Meeting 2022

Comments On The August 5th Sausalito Housing Element Update Meeting where we take a deeper look into what . . . Sausalito Housing Element Update Meeting 2022

Sausalito Housing Element Update Meeting 2022 Sausalito Housing Element Update Meeting 2022 Sausalito Housing Element Update Meeting 2022 Sausalito Housing Element Update Meeting 2022 Sausalito Housing Element Update Meeting 2022 Sausalito Housing Element Update Meeting 2022 Sausalito Housing Element Update Meeting 2022

Sausalito Housing Element Update Meeting 2022

Sausalito Housing Element Update Meeting 2022

Sausalito Housing Element Update Meeting 2022 Sausalito Housing Element Update Meeting 2022 Sausalito Housing Element Update Meeting 2022 Sausalito Housing Element Update Meeting 2022 Sausalito Housing Element Update Meeting 2022 Sausalito Housing Element Update Meeting 2022 Sausalito Housing Element Update Meeting 2022

Sausalito Housing Element Update Meeting 2022 Sausalito Housing Element Update Meeting 2022 Sausalito Housing Element Update Meeting 2022 Sausalito Housing Element Update Meeting 2022 Sausalito Housing Element Update Meeting 2022 Sausalito Housing Element Update Meeting 2022

Sausalito Housing Element Update Meeting 2022 Sausalito Housing Element Update Meeting 2022 Sausalito Housing Element Update Meeting 2022

Sausalito Housing Element Update Meeting 2022 Sausalito Housing Element Update Meeting 2022 Sausalito Housing Element Update Meeting 2022

Sausalito Housing Element Update Meeting - 5th August

Letter to Sausalito Housing Element Committee | Housing Crisis Marin County | Housing Crisis California | Housing Renovation Sausalito | Housing Renovation Crisis Sausalito | House Design Review Sausalito | Sausalito Housing Element Update Meeting - 5th August | Sausalito Housing Element Update Meeting 2022 | Sausalito Housing Element Update Meeting 2022 | Sausalito Housing Element Update Meeting 2022

Sausalito Housing Element Update Meeting - 5th August | Sausalito Housing Element Update Meeting 2022

Sausalito Housing Element Update Meeting - 5th August | Sausalito Housing Element Update Meeting 2022 | Sausalito Housing Element Update Meeting 2022

August 1, 2022

My name is Matt Smith, and my wife Kirstin and I live at 7 Harmony Lane.

We didn’t intend to undertake a construction project that would last seven years, but it has given my wife and me an extremely granular view into how the entire home remodeling process works here in Sausalito — especially concerning design reviews.

When we bought the house in 2015, it was a dilapidated structure with significant deferred maintenance, and our aim was to renovate it for our family. We finally moved in in December of 2021.

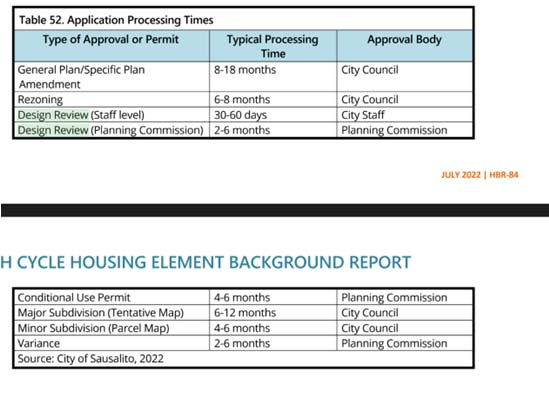

For my opinions in this note, I am leaning on the firsthand experiences we had in design review, as well as data I’ve collected on all Sausalito design reviews from 2013-2020. I’d like to specifically address Table 52 in the H Cycle Housing Element Background Report, on application processing times, and the associated note beneath it:

“While the design review requirements have not posed a constraint to development, the second

finding includes a subjective component related to “complementing” the surrounding

neighborhood. Program I6 (Zoning Ordinance Amendments) will ensure the design review criteria

are revised to address potentially subjective terminology in order to provide objectivity in the design

review process.”

Are these design review estimates accurate?

In this table, a “typical processing time” for “Design Review (Planning Commission)” is stated to be 2-6 months, and “Design Review (City Staff)” is 30-60 days. Since there is no data sourced in this table (other than “City of Sausalito 2022”), I’m assuming these figures represent some heuristic or subjective accounting of the processing time. Where did these estimates come from? What was the source? Are they based on objective facts, or do they represent someone’s best guess?

Our experience was far and away longer than these timelines.

The other troublesome framing of this data is the use of the qualifier “typical,” as in “typical processing times.” Even if the ranges presented above were based on actual project timelines, focusing exclusively on a mean or median metric is a faulty yardstick to use. What this average range does not include is the degree of variability in project timelines. Variability is what kills the developer — it adds unpredictability, and with it, financial disaster as a potential outcome.

Putting a “typical” metric out there for design review like this is inaccurate, disingenuous, and can do real harm to any sponsor of a proposed project who is trying to understand what a realistic and real-world process, budget, and timeframe would look like.

Starting with the “Design Review (City Staff)” timeframe of 30-60 days, in our case, the “processing time” was significantly longer. It took about nine months for our project to be “deemed complete.” Engineering, Public Works, and the Fire Department needed to opine on our plans. We were told by our assigned planner that, per statute, one of these departments was required to provide feedback within six weeks. But that six weeks turned into ten.

We were asked to provide a 3D rendering of a part of the proposed plans. There were questions about our title. A “colors and materials” board was requested. We had to draft a “neighborhood outreach” statement that outlined our door-to-door efforts to accommodate the needs of the neighbors, and then install story-poles at least ten days before the hearing.

Looking now to the typical processing time of 2-6 months for “Design Review (Planning Commission),” based on our experience, I would offer that a timeline of 13 months is a possibility.

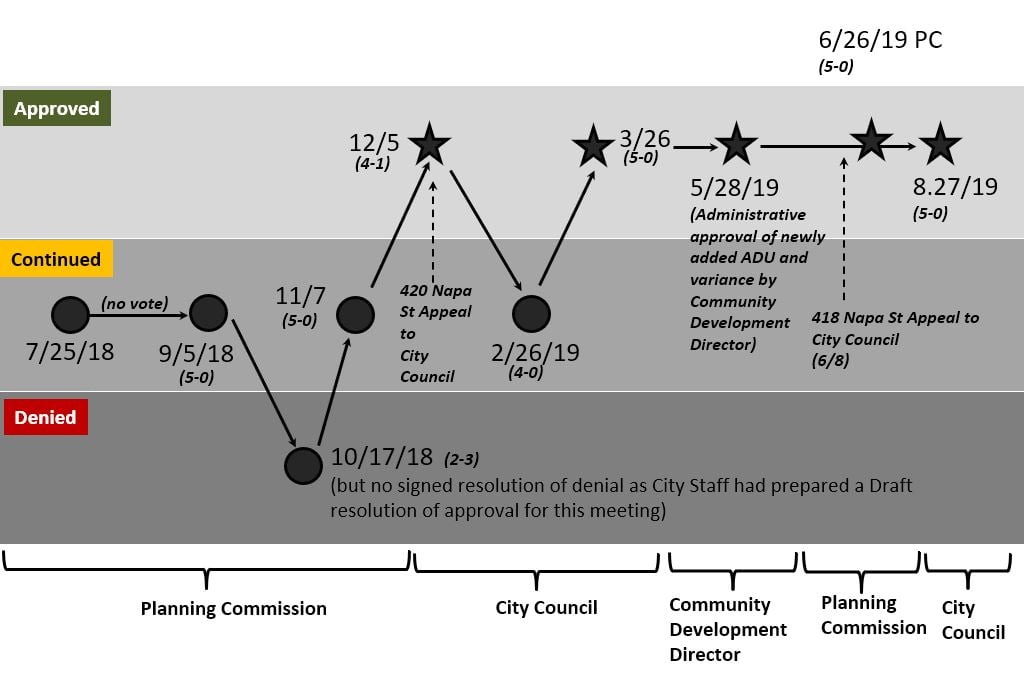

Figure 1: Design review timeline for 7 Harmony Lane

Maybe if you averaged our experience with every other design review in Sausalito, you would still get close to that time span of 2-6 months. But you’d be missing a key piece of data — the variability, i.e., the chance that you, as a developer, could run into a situation very much like ours for which the “typical” timeframes no longer apply.

In total, I, my wife, and our family were in “processing” for 13 months in design review. There were five Planning Commission meetings and two City Council meetings during this period. Six different planners that we had to bring up to speed six different times. Do we represent a “typical” project? No. But the developer/homeowner will never know if they are typical or not ahead of their design review application.

At the very least, I’d be thrilled if there was a little asterisk next to these “typical processing times.” Like this:

* Estimates presented here are illustrative only, and not based on objective data. Actual design review applications are known to take up to 9 months for an application to be “deemed complete,” and a design review being “processed” by the Planning Commission has been known to take up to 13 months.

Currently, the way project-level data is structured and stored on the Sausalito.gov website is great for meeting the requirements of the Brown Act, but it is absolutely lousy for anyone trying to understand patterns or trends.

I had a number of questions: Do heightened review projects get denied more often than non-heightened review projects? (Yes); Do the commissioners vote differently if the sponsor has an attorney with them during their hearing? (Yes); Does that improve the applicant’s chance of success? (Maybe — in this dataset there is no instance of a denial where the applicant brought an attorney).

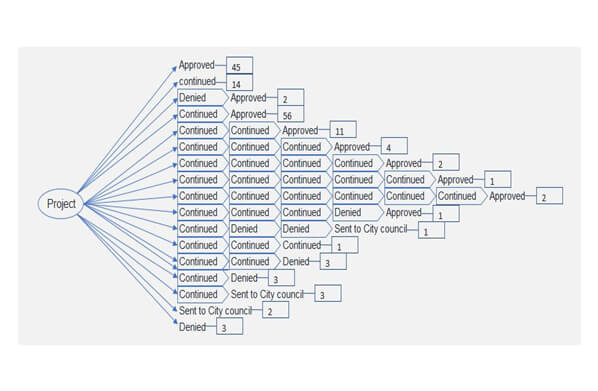

The data I needed to answer these is stored in pdf documents, and the verbal words stored in video recordings. To follow a project’s path, you have to link together all of the data from a Project ID identifier that denotes a specific application. Sometimes that Project ID isn’t there, so the link can’t be made. I know this is what’s happening (to some extent) because the figure below doesn’t include our own project, which consisted of a total of eight “nodes.” (The longest path, above, is only seven nodes in length.)

Figure 2: All design review project paths for proposed projects from 2013-2020

(Design review cases that are presented to the Planning Commission have a “DR” in their Project ID, e.g., “DR/EA/TM/TRP 13-098, Design Review Permit, Encroachment Agreement, Tentative Minor Subdivision Map, Tree Removal Permit.”)

But let’s look at what we have anyway — if anything, we are under-estimating the length of some of these projects because we can’t link all the meetings together.

We see 152 total design review paths. For 45 of those, meaning 30% of the time, there was just one Planning Commission meeting leading to a project approval. 45% of the time there are two Planning Commission meetings before an approval is granted.

So, I could agree that the “typical processing time” is probably within the 2-6-month range. But that is misleading. Let’s look at what a non-typical project might cost by using this chart to assign probabilities to a given path.

Table 1. Cost Associated with Each Proposed Project Design Review “Path”

| Number of Cycles |

Time for Each Step = 6 Weeks |

Number of Instances | % of Instances | Additional Cost / Cycle (Low, $10,000) | Additional Cost / Cycle (High, $30,000) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 6 | 45 | 30% | $10,000 | $30,000 |

| 2 | 12 | 72 | 47% | $20,000 | $60,000 |

| 3 | 18 | 11 | 7% | $30,000 | $90,000 |

| 4 | 24 | 4 | 3% | $40,000 | $120,000 |

| 5 | 30 | 2 | 1% | $50,000 | $150,000 |

| 6 | 36 | 1 | 1% | $60,000 | $180,000 |

| 7 | 42 | 2 | 1% | $70,000 | $210,000 |

| Denial* | 15 | 10% | $200,000 | $200,000 | |

| 152 | |||||

| Average Cost: | $37,368 | $72,632 |

In our case, each continuance cost at least $10,000, but more often closer to the “high” cost of $30,000.

So, we have 152 design reviews, and they are all grouped according to a given project path. Assuming each continuance cost $10,000, for example, you can see that if you had seven different Planning Commission meetings, with each one requiring a plan revision, that would end up being pretty expensive. A denial is even worse — a total loss of investment. All the money that went into your project — the work of your architect, contractors, and armies of consultants (light and shadow studies, traffic safety studies, etc.) — evaporated. Let’s assign a $200,000 value to a denial (which is low).

“I feel concerned about the bulk on the west side of the proposed project, it feels looming. I’m also terribly concerned about that garage from a safety perspective. And by the way — was a light and shadow study completed?”

This is verbatim feedback we were provided on our project. And if it doesn’t read like a clear call to action to the applicant … well, then you’re not familiar with how commissioners provide direction to applicants.

So, what does this direction mean in terms of added costs?

| Item | Cost |

|---|---|

|

Architect Fees (to trim 1 inch from the western side of the proposed house) |

$13,000 |

|

Structural Engineer (to re-run their calcs) |

$2,500 |

|

Story-Pole Plan Revisions, Installation, Validation (involves architect, builder, Geotech) |

$3,500 |

| Light and Shadow Study | $10,000 |

| Traffic Safety Study | $10,000 |

| TOTAL | $39,000 |

And in our case, it was even more, since we were floating $4,000 a month in rent to live in Sausalito while our house was being built.

What if we were to take the associated probability of a project path, its associated cost, and then take a weighted average? A SUMPRODUCT in excel?

Well, you can see that a developer would be looking at $37,000-$72,000 in extra, likely non-budgeted, costs.

And that is why a subjective design review process can be so expensive.

If I were asked, I would tell an applicant that unless they had three times the anticipated budget for their project, they shouldn’t do it.

You need to be wealthy — and privileged — to consider a project in Sausalito that involves a design review.

Again, it is critically important to be honest with would-be applicants about these design review timeframe estimates. Don’t sugarcoat it. You are doing them a disservice by lying about how long — and costly — this process actually can be.

Are Sausalito’s design review finding’s objective?

I’d like to focus on this comment beneath Table 52 of the Housing Element Background Report:

“While the design review requirements have not posed a constraint to development, the second

finding includes a subjective component related to “complementing” the surrounding

neighborhood. Program I6 (Zoning Ordinance Amendments) will ensure the design review criteria

are revised to address potentially subjective terminology in order to provide objectivity in the design

review process.”

“Design review requirements have not posed a constraint to development.”

Says who?

What data or evidence is this statement based on? What is the source?

I don’t think there is a source. I believe this statement is objectively false and should be deleted from the report.

On October 17, 2018, our project was scheduled for a design review hearing (our third). It was a very tense meeting, and the chair of the Planning Commission was upset and extremely agitated about the phased approach we had taken.

He opined (the text below is verbatim from that meeting):

“I have empathy for the Applicant and the process, and the time, and the money, but that’s not our fault. Our fault is described by the Sausalito Municipal Code and at the direction of City Council to protect Sausalito, to make sure when development occurs under not only just the literal definition of what we find here but also the spiritual information we get from the General Plan …”

(“Spiritual information.” Huh. Where can I, the applicant, go to understand where the “spiritual information” is in the general plan?)

What followed was a discussion between the chair and another Planning Commission member on the “vibe” and “feel” of the street where our house was located.

City staff had prepared a Draft Resolution of Approval for our revised plans, ready to sign at this meeting. But in the end, the Planning Commission went in the opposite direction from their staff. The final vote count was 3-2 in favor of denial. The findings that could not be met were Finding 7 (“The design and location of buildings provide adequate light and air for the project site, adjacent properties, and the general public”) and 13 (“The project has been designed to ensure on-site structures do not crowd or overwhelm structures on neighboring properties”).

City staff was directed to delete their Draft Resolution of Approval and create a Draft Resolution of Denial for the next meeting for the commissioners to sign.

And then there it was a few weeks later, the Draft Resolution of Denial for our proposed project. With some revisions on whether or not Findings 7 and 13 could be “met.”

In the earlier Draft Resolution of Approval, the conclusion on Finding 7 was that “Overall, the neighborhood has an eclectic mix of separation distances between structures and as designed, the project will maintain adequate light and air for the project site, adjacent properties, and the public.”

But on the subsequent Draft Resolution of Denial, the city staff revised their language on Finding 7:

“The two-story western addition, as designed, is a significant structural presence with scale, mass, and bulk that impedes the maintenance of adequate light and air for adjacent properties, particularly the neighboring property to the west.”

This finding was now not met.

City staff had written earlier that Finding 13 could be “met”:

“The project has been designed to not crowd or overwhelm neighboring structures. Exterior walls incorporate façade articulations and offsets on both levels and at every side of the residence. The roofline is varied with the western addition having a recessed and subordinate roofline.”

But in the latest version, that language was revised to characterize a diametrically opposite opinion.

“The project’s impacts to the built environment include the crowding and overwhelming of neighboring structures, particularly the westerly-adjacent property. The façade articulations and offsets on both levels of the two-story western addition are insufficient and require a redesign to alleviate congestion for the project site, adjacent properties, and the general public.”

But the most fascinating part of the story is what happened next. On November 7, our proposed project was supposed to have its final Planning Commission meeting, as the Draft Resolution of Denial was now there for the commissioners to sign. For all of the previous hearings we had been to, we had offered a design change consistent with the commissioners’ feedback. This time we offered nothing different from what had been presented previously. When it came time for the commissioners to opine, then sign the denial, something unexpected happened. One of the commissioners who voted against our project earlier spoke up:

“As I spent more time walking around the area, I was blown away by the proximity of all the homes in the area. It is a very tight area. And some of my expectations for Findings 7 and 13 were shifted slightly as I spent some time there and I saw just how close everything is.”

She could now “make the findings.”

With a preamble regarding the unique character of Sausalito, another commissioner who voted to deny our project earlier offered, “I could be able to make the findings.”

I thought about it the next morning, sipping coffee and reflecting on the odd way these commissioners’ made decisions.

It was fascinating — we had provided absolutely no new design for this meeting, offered no additional concessions, had done absolutely no re-work for this hearing like we had before. The only thing that was different was that these two commissioners, by site visits, realized for themselves what we had been trying to tell them. Information we had already provided to them.

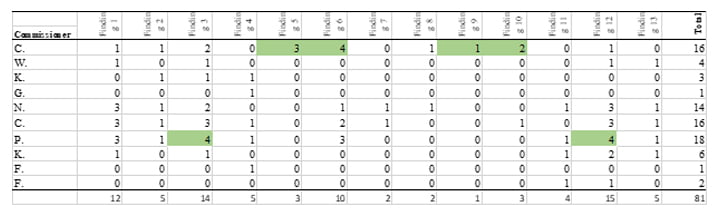

Are Findings 7 and 13 the most popular findings that cannot be “met” in Sausalito?

As it turns out, out of 152 design review meetings, I was only able to isolate 81 stated findings that could not be met among a handful of design review cases from 2013-2020.

Findings that can’t be met are extremely poorly documented, which is yet another separate problem (commissioners should be publicly stating the rationale for their vote by citing findings and then the facts that led them to not be able to “make” the findings).

Table 2. Unmet Specific Findings Stated by Planning Commissioners

My hypothesis was that planning commissioners would gravitate toward the more subjective findings, such as “crowding,” “loss of light and air,” and “privacy to adjacent properties,” versus the seemingly more objective ones, such as “inconsistent with general plan” and “does not meet requirements of heightened review.”

Hearing commissioners opine, “It feels greedy,” “I feel like this house needs to go on a diet” (these are real quotes from real design review sessions), I had to believe 7 and 13 were the best findings to “not meet.” They lend themselves well to those sentiments in quotes. How can an applicant debate with a commissioner who uses “light and air” as an objection?

But I was wrong — at least with this limited dataset. The first and third most common findings to not be met were “Inconsistent with the General Plan” (1) and “Heightened Review findings not met” (12), which surprised me, because these findings are based on the guidelines of codified documents, and thus seemingly more objective.

But then I realized these two findings have “nested findings” within them that allow a commissioner to be even more vague, because all they have to say is, “It’s inconsistent with the general plan.” That’s it. They don’t need to cite which aspect of the general plan isn’t met.

The other nested finding, Finding 12, gives a planning commissioner access to seven more findings — for example, excessive “crowding of neighboring structures.” And in the case of Finding 12, Heightened Review, it carries with it the veneer of a quantitative finding, as it only applies to proposed structures with building coverage or FAR at or above 80% of what is allowed. Things feel more real if you can measure them by numbers, and that’s what this arbitrary 80% figure does.

So, in choosing one of those two, a PC member can access a plethora of other reasons to continue or deny the project.

The “Denial Toolkit” of Findings 1 and 12 offers an extensive range of reasons to back into a “spiritual” discomfort with a given design.

Do the planning commissioners tend to vote in the same way?

Looking at design review decisions across all planning commissioners from 2013-2020, the answer is no.

Some, like Commissioner “K.,” don’t like to vote to continue as much as the others. And what applicant wouldn’t want Commissioner F., K., and G. (and just those three) to vote on their proposed project?

Table 3: Planning commissioners and approval percentage, 2013-2020

| Planning Committee Member | Approval Percentage | Denial Percentage | Continued Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| F | 71.4 | 0.0 | 28.6 |

| K | 55.1 | 8.2 | 34.7 |

| G | 55.0 | 2.5 | 40.0 |

| P | 54 | 7.1 | 38.1 |

| F | 53.6 | 7.1 | 35.7 |

| N | 47 | 5 | 43.6 |

| W | 46.3 | 6.7 | 41.8 |

| C | 45.8 | 7 | 45.8 |

| K | 45.3 | 6.7 | 41.3 |

| C | 42.1 | 5.3 | 45.6 |

The Planning Commission has five members serving at any given time, but only three are needed to be able to vote on behalf of the committee.You might wonder — do the commissioners vote differently?

What if one who tends to approve proposed projects is sick that night, or on vacation and not present on the dais?

That would seem to skew your chances of approval in the wrong direction, right? Correct.

Table 4: Attendance Rates of Planning Commissioners, 2013-2020

| Commissioner | Years Active | Attendance Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|

| C | 2013 - 2016 | 89.6 |

| W | 2013 - 2018 | 73.4% |

| K | 2013 - 2015 | 53.7% |

| G | 2018 - 2020 | 93.3% |

| N | 2013 - 2020 | 98.2% |

| C | 2013 - 2017 | 83.1% |

| P | 2015 - 2020 | 84.1% |

| K | 2016 - 2020 | 60.9% |

| F | 2019 - 2020 | 90.3% |

There was one meeting where the absence of a particular City Council member likely tipped the outcome in our favor.

There was another meeting where the presence of a certain Planning Commission member shifted the balance away from us.

That’s just the way it works.

Sometimes you’re lucky, sometimes you’re not.

Does the City Council back the decisions of its Planning Commission?

Not as much as you would expect. Or hope.

Table 5: Activities of City Council Members

(Approved a Planning Commission Denial / Denied a Planning Commission Approval)

| City Countil Members | Approved a Planning Commission Denial | Denied a Planning Commission Approval | p-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | TOTAL | Yes | No | TOTAL | ||

| CC1 | 4(30.8) | 9(69.2) | 13 | 10(58.8) | 17 (41.2) | 17 | .127 |

| CC2 | 13(100) | 0(0.0) | 13 | 17(100) | 0(0.0) | 17 | - |

| CC3 | 5(38.5) | 8(61.5) | 13 | 6(35.3) | 11(64.7) | 17 | .858 |

| CC4 | 2(16.7) | 10(83.3) | 12 | 10(58.8) | 7(41.4) | 17 | .023 |

| CC5 | 1(7.7) | 12(92.3) | 13 | 1(5.9) | 16(94.1) | 17 | .844 |

| CC6 | 8(61.5) | 5(38.5) | 13 | 5(29.4) | 12(70.6) | 17 | .078 |

| CC7 | 11(84.6) | 2(15.4) | 13 | 11(64.7) | 6(35.3) | 17 | .222 |

| CC8 | 6(46.2) | 7(53.8) | 13 | 7(41.2) | 10(58.8) | 17 | .222 |

| CC9 | 1(7.7) | 12(92.3) | 13 | 6(35.3) | 11(64.7) | 17 | .077 |

Generally (in aggregate), it’s a coin toss, but it varies by City Council member.

The pride of authorship rides high in Sausalito — everyone wants to etch their mark on a proposed project in design review. The mistake we had made with our project — after a neighbor appealed our approval — was assuming that the City Council would back the decision of their Planning Commission. Our architect had given us some wise words that my wife and I didn’t fully appreciate at the time: “They [the City Council] will want their pound of flesh too.”

If an applicant’s design is appealed by a neighbor, that applicant had better get ready for another entirely new design review with the City Council. They are all different, and they all have their own point of view when it comes to “making the findings.”

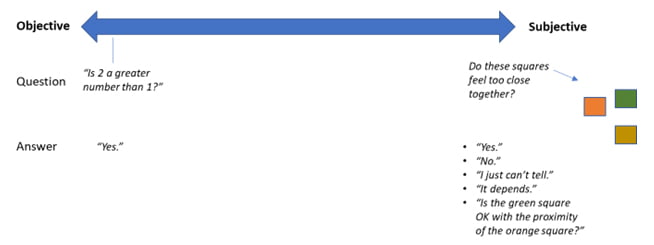

The question – is the design review process objective?

If the design review standards are so objective, and so clearly and equally understood by all Planning Commission members, as well as the City Council, then why is there so much variability in their voting records? Why can some “make the findings” and others not in reviewing a proposed project? Why wouldn’t they all be able to “make the findings” or not in the same way? Or vote the same way?

If your answer is, “Well of course they vote differently, they each can independently make or not make certain findings, they are different people with different opinions” … Well, then you have your answer. If the commissioners’ votes are attributed to their personal opinions, judgments, or points of view, you are aligning yourself to a subjective orientation in terms of how a given proposed project should be evaluated.

The very nature of how these subjective findings are worded is destined to provide a high level of variability in commissioners’ answers.

Figure 3. Objective vs. Subjective Questions

(An Example)

An objective question has an objective answer, one based on facts, logic, and data. There is only one correct answer.

All of the subjective answers above are valid. A subjective question gives rise to a subjective answer, which will vary from person to person.

And that is why there is so much variability in voting records.

My takeaway is that it is the subjective and loosely defined Findings for Design Review that are driving the unacceptable level of variability in the voting decisions, causing confusion among applicants, and adding unnecessary resource expenditures to the process.

Additionally, as per the data discussed here, I believe that the following factors have a very real influence on design review decisions:

- Presence or absence of a given Planning Commissioner

- The influence that a given commissioner has on the vote of the other commissioners

- Availability and ability to use “nested” findings to deny or continue a proposed project

- How the commissioner interprets what a given finding means

- How the commissioner applies their understanding of the findings to the proposed project

- The commissioner’s likelihood to take action (an approved or denied vote) versus a continuation

- The extent to which a City Council will uphold or vacate a Planning Commission design review decision

In Closing

My other takeaway is that the way Sausalito documents its design review data is actively helping the city obfuscate what appears to be a haphazard and subjective decision-making process from those who wish to understand and improve it. It took me hours upon hours to distill the data used in the analyses above.

With the goal of increasing transparency in design review decision-making, I would request that city staff begin documenting findings that could not be met (with facts in the rationale) along with the vote for every Planning Commission member who is voting on a design review.

And that is my official commentary on those three pieces of the Housing Element Background Report that caught my eye.

Thank you for reading this commentary.

While You're Here . . .

But, well, since I’m here anyway, I might as well share one more story.

I’ll start with this quote:

“You said that the President sometimes communicates his wishes indirectly … can you explain how he does this?”

“Sure … he speaks in code. He doesn’t give you questions; he doesn’t give you orders. He speaks in code, and I understand that code.” – Michael Cohen, disbarred lawyer

Sounds like how the mafia gives direction, right? But it’s also eerily similar to how “feedback” is provided to an applicant.

Consider this quote — specific to a review of our proposed project at 416 Napa St. — from the then-mayor of Sausalito, opining to city staff and explaining his homebrewed, gerrymandered analysis. Consider also his direction to us, the applicants.

“Did you, in your analysis, separate houses that were multi-family from single-home family in your local FAR analysis? If we’re being truthful, the neighborhood doesn’t include this street here, that’s another neighborhood. So, when we look at contrasting and comparing neighborhoods, that’s what we’re looking at.

“Since this fall into the realm of discretion, and I’m looking at neighborhood character, I want to compare it to the properties I think are most relevant.

“So, I pulled up the comps that I think are the most relevant, and there’s about 98 homes in there in this neighborhood … Now, where we would have more discretion is if someone was doing a multi-family residence. That is the goal. So, we’re really talking about that top level and fourth bedroom, and how needed that fourth bedroom is, or how needed or relevant that bedroom is if it’s not proposed as a multi-family four-bedroom home — that’s where I went. This is an R-3, and we have the opportunity to make this house at least an R-2.”

Now, if you were the applicant here, what would you think this City Council member was trying to tell you? This is how it works — they “talk” to each other up there, but they are really giving you orders. Remember, they have the power to continue or deny your project. That “discussion” up there is meant for your — the applicant’s — ears.

And that is how our fourth bedroom turned into an Accessory Dwelling Unit.

If I could go back in time to the spring of 2015, I would have told myself to run away from 416 Napa St. and instead figure out a way to beg, borrow, and steal enough resources to be able to buy a move-in-ready home that fit the needs of our family. The stress, financial strain, and damage that this seven-year ordeal caused me and my family was so far beyond even the worst-case scenarios that I could have imagined at the time.

But that’s the past. It’s now 2022, and we are living in our home. All that work, stress, and spent money is behind us. And now we’re here. For the last four years prior to moving in, we had been renting in Sausalito. Our oldest son thrived at Bayside MLK and is doing great at the newly integrated school.

Our youngest will attend the same school in about a year. My wife is playing an ever-increasing role in the school system. Our family had a great time at the most recent Fourth of July festival — this town knows how to throw a party! We look forward to getting the boys out on the water, to hiking the trails of GGNRA, to continuing to frequent the great local cafes and restaurants. We are putting roots down and want this town to thrive.

When I look at Marin real estate listings and see distressed, half-built homes being sold by distressed homeowners, I feel bad for them. Obviously, it is not the intent of someone starting a major home remodel to abandon it halfway through. Did the marriage break up, with the unfinished house having to be sold? Did the house bankrupt the homeowners? Did the stress of the remodel destroy the marriage?

There are real people out there. Real lives. I know that the work the HEC is doing might feel abstract and potentially intangible — word-smithing the language of findings, tweaking bits of code — but your final result, the final document, will very much have a tangible and very real effect on homeowners like my wife and me who wish to improve their property for their family.

When you open the door to objectivism, you let in facts, numbers, and logical conclusions. When you open the door to subjectivism, you let emotional and political variables into your decision-making. And their cousins — hyperbole and gaslighting.

And so, I urge the Housing Element Committee to please learn from our story, look to real-world data for answers, and wherever possible, please, please, please build a bias in your thinking toward objectivity and objective design standards for proposed projects.

Thank you,

Matt H. Smith